Summary

This is part of our series of Patient Safety Spotlight interviews, where we talk to people working for patient safety about their role and what motivates them. Gordon talks to us about how bureaucracy in the health service can compromise patient safety, the vital importance of agreed quality standards and what hillwalking has taught him about healthcare safety.

About the Author

Gordon was a medical student at Oxford University and King's College Hospital London. He completed postgraduate training in Medicine, Diabetes and Endocrinology and was a Consultant in Worthing from 1993 to 2018 and in Oban from 2018 to 2022. Gordon developed a process and safety checklist for ward rounds and brought the Royal Colleges of Medicine and Nursing together to publish recommendations on best practice for ward rounds.

Questions & Answers

Hi Gordon! Please can you tell us who you are and what you do?

I’m Gordon and since stopping clinical work in October last year I work for NHS England Emergency Care Improvement Support Team (ECIST). Before this, I was a Consultant in General Medicine, Diabetes and Endocrinology at Worthing Hospital from 1993 to 2018, where I was also Director of Medical Education. From 2018 to 2022 I worked in the small rural general hospital in Oban on the west coast of Scotland, where I continued my work in healthcare safety and training clinical staff. I have particular expertise in the use of computers in direct clinical care at the bedside and in outpatients.

How did you first become interested in patient safety?

When I started my clinical studies at King's College London in 1977, there was an emphasis on making the correct diagnosis for patients and the avoidance of iatrogenic harm. Although it wasn’t called patient safety in those days, there was a strong awareness of medication and treatment as agents that can cause disease.

Looking back through my career, I particularly remember three patients who alerted me to the need to address healthcare safety issues in a more organised manner.

The first was a man in his 70s with COPD who had been successfully treated for pneumonia with IV antibiotics. I saw him on a ward round about a week after he had been admitted to hospital and he asked me what was wrong with his left arm. When he rolled up his sleeve he had a cannula hanging out of his arm surrounded by an area of infection. He had an MRSA infection that had spread to his blood, which meant he had to be treated for septicaemia in hospital for a further two weeks. The MRSA could have been avoided completely if the cannula had been taken out when the IV treatment was stopped. It struck me that we can have very successful, high tech treatments in medicine that are undermined by seemingly mundane issues like whether a cannula is taken out.

The next patient was a man who had known anaphylaxis to penicillin, which was clearly documented in his GP and referral notes and on the hospital pharmacy chart. In spite of this, a doctor prescribed him penicillin for pneumonia and nurses administered it. He had an anaphylactic reaction and nearly died. In spite of having all the red flags in place, he was given the wrong treatment. It made me think further about how we can make systems safer.

The third patient that really stayed with me was an outpatient I saw right at the end of a busy clinic. As an endocrinologist, it should have been very easy for me to diagnose her with Addison’s disease, which is a condition where the body doesn’t make any steroids. However, I managed to completely miss the diagnosis and about three months later the woman contacted me to tell me she had nearly died as a result. I went back through her case and considered why I failed to diagnose her correctly. That’s when I became interested in human factors—the environmental and context issues that can undermine clinical reasoning and harm patients. In this case, there were a number of factors that had an impact: I was carrying the caseload of two consultants on my own, managers had forgotten to advertise for a locum position, appointment times were too short and clinics were too long. I was under pressure and distracted by an unmanageable workload, which meant I didn’t concentrate properly on the patient in front of me.

Tell me about a time in your career that you found fulfilling

When I worked at Worthing, I began thinking about establishing a fixed routine for reviewing potential safety issues for each patient on our ward rounds. Together, our team came up with a checklist that we agreed we’d do for every patient. It came about after an FY1 doctor had run the Monday morning ward round and said to me, “That was great, but how do I know whether I’ve done everything?” I realised that we hadn’t considered what ‘doing everything’ was, so I invited them back on Wednesday lunchtime to decide together what ‘doing everything’ looked like. Using our discussion, I developed a checklist we could use on ward rounds which we tried out that Friday. I asked our medical student to use the checklist, reiterating the importance of their role.

I found the enthusiasm of the registrars and other junior doctors in the team really rewarding. Alongside our nursing staff, the whole team was willing to experiment, try things out and try again if it didn’t work. The team saw that it made sense and made a difference—ward rounds felt much more organised as everyone knew what was happening next for every patient. Having someone checking that we had covered everything was a great relief because it meant I had the mental capacity to deal with the headline issues, knowing that someone was watching and would tell me if I missed anything.

I was able to train the other doctors in the team in this routine and they often took the ward rounds while I did the checking. Unfortunately, this collaborative approach isn’t embraced everywhere and we had to warn our medical students that many consultants wouldn’t feel it was the place of students to be making comments about what they had missed!

How can introducing standards improve patient safety?

Overt, agreed standards that make sense to everyone improve safety. The checklist gave us a clear process which made it much easier for whoever was checking to speak up if the doctor taking the ward round missed something, regardless of their seniority. I was very careful initially to ensure I turned to the checker at the end of each patient and asked them if we had done everything on the list. An important part of the process was understanding we’d get it wrong and need to change what we were doing—we must have been through over 300 versions of the checklist by the time I finished my ten years at Worthing.

Another example of this was introducing standards on the ward to ensure prescriptions were legible. We included principles like always using capitals and writing out micrograms/milligrams in full. If a doctor was filling in a prescription chart on a ward round and it wasn’t done according to the standards we’d agreed, we’d get them to change it there and then. This simple intervention transformed the standard of prescribing in our team within three or four weeks.

What patient safety challenges do you see at the moment?

One of the biggest patient safety issues I see is the way the Government, NHS leaders and the media see productivity simply as numbers. For example, targets to see patients in A&E within four hours or for cancer patients to start treatments within a certain number of weeks. These number-based targets don't place proper emphasis on safety, quality and efficiency— I’ve seen patients hustled out of A&E just before four hours are up because the management wants to hit a target, rather than because it’s appropriate for their clinical care. Particularly as we come out of the pandemic and there is an emphasis on ‘catching up’, the NHS seems to be focusing on how much clinical work can be done, rather how much work can be done safely, or how we can improve efficiency. The message is that everyone has to work harder.

This pressure means that other activities that benefit patient safety are sidelined. Over my career, I’ve noticed a decline in meetings where colleagues discuss difficult cases and harm—they either don’t happen now or are very poorly attended. For example, morbidity and mortality meetings and ‘ground rounds’, where a consultant presents their difficult cases for discussion with colleagues, are deprioritised as there’s so much pressure to be doing clinical work all the time. Around the year 2000, I stopped having lunch breaks, and lunch is one of the most important times for patient safety. If doctors are sitting together and eating, they will talk about their difficult patients and errors they have made and share learning and advice.

What role do information systems and paperwork play as barriers to, or enablers of, patient safety?

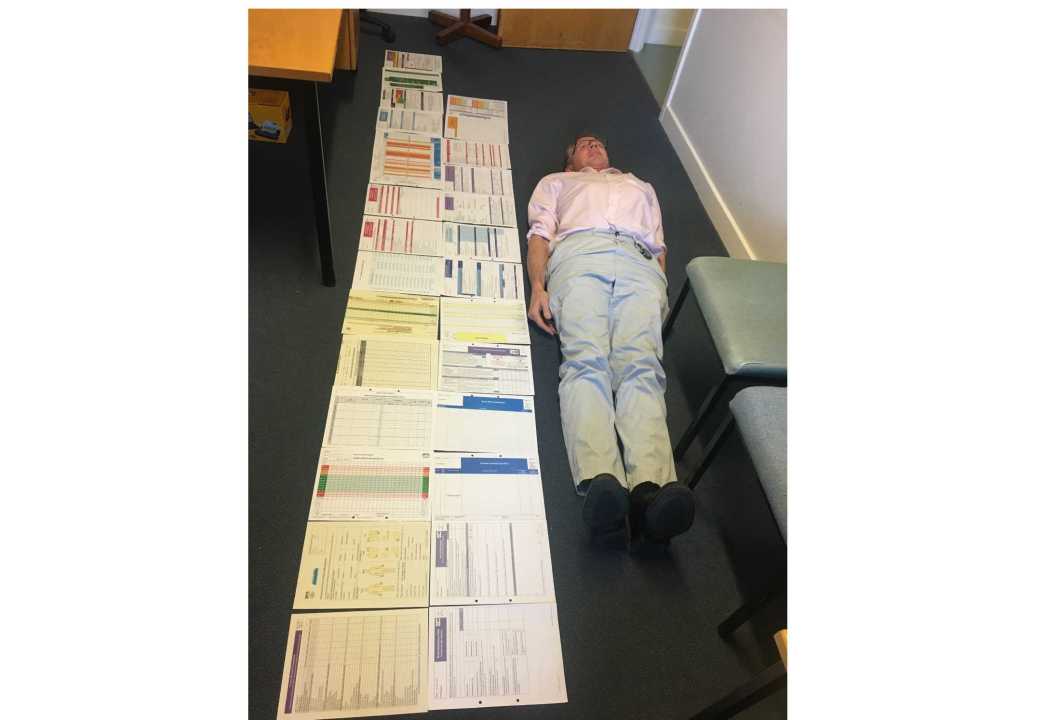

There is a widespread belief in the NHS that bureaucracy solves problems. You might have seen the picture of me lying on the floor lying next to the 30-40 sheets of paper that a nurse has to fill in by hand for each patient admitted to Oban hospital.

It can be even worse on a computer because the screen looks nice, but there can be as much or even more mess behind it. Each one of those forms might have a good intention, but because there’s so many of them and all the information is entered manually or retyped, they are full of errors, inconsistencies and omissions. Bureaucracy distracts from clinical care, as it takes clinicians’ mental capacity away from patients. We need to do away with the idea that form filling=care. Documentation needs to be designed so that it matches the pace of care, which is what we were aiming to achieve with our ward round checklist.

I’m also very concerned about the severely disjointed information systems we have for direct clinical care. Take a patient who has three or four diagnoses and takes maybe ten medications—their GP will send this information to the hospital as a PDF or even a fax, where a doctor or nurse rewrites it, potentially making errors. When I moved to Scotland I realised that there is no digital communication between NHS England and NHS Scotland, and that’s a big safety issue. If a patient with a penicillin allergy who lives in England arrives unconscious with sepsis at Oban Hospital, there’s no way for medical staff to know about their medical history and they could well give the patient a penicillin-based antibiotic and kill them. It’s actually easier to look after a patient from the US than a patient from England, because US patients can pull out their mobile phone and show me their whole clinical record and contact details for their specialists, while patients from England can show me nothing. This lack of communication between systems makes care inefficient, prone to error and dangerous for patients.

What do you think the next few years hold for patient safety?

I’m pleased to see that NHS England is putting great emphasis on patients being able to access their own healthcare information. NHS England’s intention is to use the NHS app to open access up further so that patients will be able to see pretty much everything that’s held about them on their GP’s database. I think that’s entirely appropriate—giving patients access to their own records and allowing them to give their partner or relative permission to view their records could be a huge step forward for patient safety.

In the UK, we have a paternalistic attitude to clinical information as a profession and as a society, and changing that will greatly improve patient safety. There’s a lot of talk about ‘empowering patients’, but I think it’s just the way it should be—if our banks didn’t allow us to see our bank statements and transactions we’d think that was crazy!

We also really need to see a change in the culture of the healthcare system so that it is accepted and expected that anyone can speak up about safety issues, no matter their grade or position. The NHS’s reputation for bullying and treating whistleblowers badly has to change if we’re serious about improving safety. In the ten years since Mid Staffs, there seems to have been little change in NHS culture. It’s very difficult to understand why change hasn’t happened and why we’ve tolerated it not happening.

If you could change one thing in the healthcare system right now to improve patient safety, what would it be?

I would ensure we build our information systems around the patient rather than around services. Allowing the patient to have access to their information is one part of that, the other is having the ability to transfer patient information between general practice and the hospital so doctors don’t spend the first ten minutes of a consultation clarifying already-known information and correcting errors in it. An information system built around the patient would free so much capacity for thinking and make the whole system more efficient and safe. Unfortunately, it’s a huge undertaking and I don’t think it’s going to happen in NHS England as each hospital has developed its own information system.

If I’m allowed one extra thing, it would be to get each healthcare team to decide together on just three points they will consistently check for each patient. A simple intervention like this would reduce errors and help change the idea that the consultant is ‘god’ and must never be challenged.

Are there things you do outside of work that make you think differently about patient safety?

I enjoy hillwalking, sea kayaking and gardening, where I fell trees and split logs—in all of those areas you need to address safety in context as an integral part of the behaviour. If you're going out for a walk in the hills you have to anticipate what might go wrong: If the weather changes quickly, what will I do to get down safely? Have I got my locator beacon and flares?

It’s about thinking sensibly about what might go wrong and putting a plan in place, and this is something I have brought to my thinking on patient safety. An example of this is when we introduced a simple measure on our morning ward round for overnight admissions. Sometimes a cardiac arrest bleep would go off in the middle of the round and suddenly I’d be standing there with no doctors because everybody went to deal with the cardiac arrest. So we started to state at the beginning of each round that if the bleep went off, the registrar would go, and if they needed support they would contact us. It made such a difference to the ward round as it meant that we all carried on with the work if something unexpected happened.

Tell us one thing about yourself that might surprise us!

I enjoy cooking, and if I’m making a crumble up here in Scotland, I use porridge oats rather than plain flour and it makes a lovely flapjack topping—it’s much better than a floury crumble!

Related reading

Active patient safety checking during the ward round: a blog by Dr Gordon Caldwell

0 Comments

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now